Girard College

2101 S. College Avenue, Philadelphia

“No other American school was born amid such thunderous echoes as were heard at the founding of Girard College. Stephen Girard died in the closing days of 1831 and he was America’s wealthiest citizen. Nearly the whole of his fortune, or about $7,000,000, was bequeathed to Philadephia for the one purpose of building and maintaining a college for fatherless boys.” (Herman LeRoy Collins, A.M., Litt D., Philadelphia: A Story of Progress, volume 2, Philadelphia: Lewis Historical Publishing Company, 1941: 79)

“The cornerstone of the new Girard College was laid in 1833 but it was fourteen long years before its doors were opened to orphan boys. The original building, architected by Thomas U. Walter (“the grandfather of whom, Jacob Friedrich Walter, had immigrated from Germany”), (German Achievements in America: Rudolf Cronau’s Survey, Don Heinrich Tolzmann, editor, 1995: 202) cost almost $2,000,000. It remains today the finest example in America of a reproduction of chaste Greek architecture.” (Herman LeRoy Collins, A.M., Litt D., Philadelphia: A Story of Progress, volume 2, Philadelphia: Lewis Historical Publishing Company, 1941: 81)

The Biddle Andalusia Estate on the Delaware River

The Biddle’s Andalusia estate was also architected by Thomas U. Walter. (Herman LeRoy Collins, A.M., Litt D., Philadelphia: A Story of Progress, volume 2, Philadelphia: Lewis Historical Publishing Company, 1941: 244)

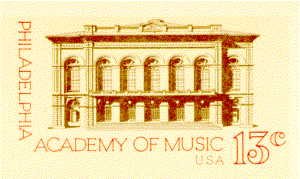

The Academy of Music

Broad and Locust Streets, Philadelphia

German artistic influences can be found throught the Academy of Music, where some of the world’s most acclaimed composers, like Tchaikovsky, Richard Strauss, Stravinsky, Rachmaninoff and Gershwin have performed. In 1855, Napoleon LeBrun, an American, and Gustavus Runge, a German, were selected as the architects for the Academy of Music. “This jewel, which fairly glitters when the lights are up, is sumptuous enough to rival those of the kingdoms, principalities and duchies of middle Europe, those opera houses built for the gratification of their rulers — kings, princes, grand dukes, electors, royal and serene highnesses.” (John Francis Marion, Within These Walls: A History of the Academy of Music in Philadelphia, Philadelphia, 1984: 13)  The four large murals on the domed ceiling , 70 feet above the parquet circle, which depict poetry, music, dance, comedy and tragedy, as well as the four seasons, were painted by Karl Heinrich Schmolze, a native of Zweibrücken, Germany. (Kay Mott, “Forgotten Painter: Murals on Academy ceiling are by Schmolze”, Inquirer Magazine, 5-13-57 and John Francis Marion, Within These Walls: A History of the Academy of Music in Philadelphia, Philadelphia, 1984: 13, 33) “A German scene painter from Berlin, J.R. Martin, worked on the interior apartments.” (John Francis Marion, Within These Walls: A History of the Academy of Music in Philadelphia, Philadelphia, 1984: 39) The cornerstone was laid on July 26, 1855 with President Franklin Pierce in attendance. (John Francis Marion, Within These Walls: A History of the Academy of Music in Philadelphia, Philadelphia, 1984: 38) A grand ball opened the Academy of Music on January 26, 1857.

The four large murals on the domed ceiling , 70 feet above the parquet circle, which depict poetry, music, dance, comedy and tragedy, as well as the four seasons, were painted by Karl Heinrich Schmolze, a native of Zweibrücken, Germany. (Kay Mott, “Forgotten Painter: Murals on Academy ceiling are by Schmolze”, Inquirer Magazine, 5-13-57 and John Francis Marion, Within These Walls: A History of the Academy of Music in Philadelphia, Philadelphia, 1984: 13, 33) “A German scene painter from Berlin, J.R. Martin, worked on the interior apartments.” (John Francis Marion, Within These Walls: A History of the Academy of Music in Philadelphia, Philadelphia, 1984: 39) The cornerstone was laid on July 26, 1855 with President Franklin Pierce in attendance. (John Francis Marion, Within These Walls: A History of the Academy of Music in Philadelphia, Philadelphia, 1984: 38) A grand ball opened the Academy of Music on January 26, 1857.

The Fairmount Waterworks on the Schuylkill River

“Frederick Graff, whose battered and neglected monument stands between the Water Works and the rocky slope of Fairmount, was one of Philadelphia’s great civil servants before that term was invented. His grandfather, who came from Germany in 1741, and his father before him had been skilled master builders and contractors. On April1, 1805, Graff was made superintendent and engineer in charge of the works. He was to serve the city for forty-two years and to become the leading American expert on hydraulic engineering. Graff created for the Water Works a new technology for control of the movement and delivery of water: iron pipes replaced the old piping of wooden logs; fire hydrants to which the fire engines could be directly connected, stopcocks to stop the flow of water in case of a leaking or broken pipe. His advice and innovations were followed by about thrity-five American cities and drawings of them sent to England. Within two years the use of Schuylkill water and the handsome buildings by the river that housed the Water Works were the pride of the city. (Mary Maples Dunn and Richard S. Dunn, Philadelphia, New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1982, 228 – 230)

“Throughout most of the 19th century The Water Works provided a continuous supply of potable water to Philadelphia using, successively, steam engines, water wheels and water turbines. The pavilions and mill house facades, built as screens for these mechanical wonders, were added in stages by Graff, and his son Frederick Graff, Jr., to accommodate the Works’ engineering progress. As such they are a composite of Federal and the many popular Revival styles of design – Tuscan, Gothic, Greek and Roman – which punctuated the early and mid 19th century.” (Fairmount Park Art and Architecture Guide Series, Fairmount Park Commission, 1995)